Public media faces a future of rapid structural changes. Federal support has been rescinded, state funding is inconsistent, and hundreds of local stations, especially in rural areas of the country, risk going dark. Yet public sentiment remains more supportive than the political headlines suggest. A 2025 national survey found that U.S. voters trust public media more than media overall and view it more favorably than for-profit outlets. At the same time, how people find, consume, and trust information is fundamentally changing. Half of U.S. adults under 30 now trust national news organizations and social media personalities at roughly the same level; many say the voices they rely on most are individuals who they consider more “authentic,” responsive, and relatable.

Public media sits at the intersection of institutional vulnerability and a rapidly shifting information ecosystem: it is trusted by the public yet increasingly competing with new voices and platforms for attention and relevance. In this context, a group of leaders from media, philanthropy, and research met in November in Washington, D.C. to imagine its long term future. A summary of the discussion follows.

Welcome & Framing

Vivian Schiller (Vice President & Executive Director, Aspen Digital and former NPR President & CEO) opened the session urging participants to think beyond institutional muscle memory. She stressed that the purpose of the meeting was to confront public media’s “highest calling: serving the information needs of the American people to preserve democracy” and to do so without being burdened by the structures built in a different era. The recent loss of federal support, she noted, was “not the cause… but the catalyst,” a forcing event that makes long-term design questions unavoidable.

Gary Knell (Senior Advisor, Boston Consulting Group and former NPR President & CEO) provided historical context. Drawing on a century of public broadcasting history, he compared the moment to “the Palisades fire… now we have to think about how we want to rebuild this community.” Federal support, he reminded the group, was “an enabler, not a definitional requirement”: the core of public media has always been its noncommercial mission, not its appropriations. The question on the table was not how to resurrect past structures but “how to live without this center of gravity” and design a system suited to the next generation.

“We’re out of time. The world is moving so fast that our institutions are not keeping up… never let a crisis go to waste.”

– Laura Walker | President of Bennington College and former President & CEO of New York Public Media

Laura Walker (President, Bennington College and former President & CEO of New York Public Media) urged the group to use the crisis as an opportunity for clarity. “We’re out of time. The world is moving so fast that our institutions are not keeping up… never let a crisis go to waste.” Students she engages with expect three things: free access, trust, and authentic connection. “Public radio and TV sound stale,” she said, reflecting their feedback. Her challenge to the room—“take off your uniforms”—became a refrain throughout the day: what would we build if we were inventing public media now, without legacy constraints and structures?

Scene-Setters

Participants heard a set of scene-setting briefings that mapped the terrain: the decline of local news; the vulnerability of the system without federal funding; the emerging policy environment; shifting media consumption behavior, and the philanthropic landscape. These short presentations established the stage for the discussions that followed.

The State of Local News

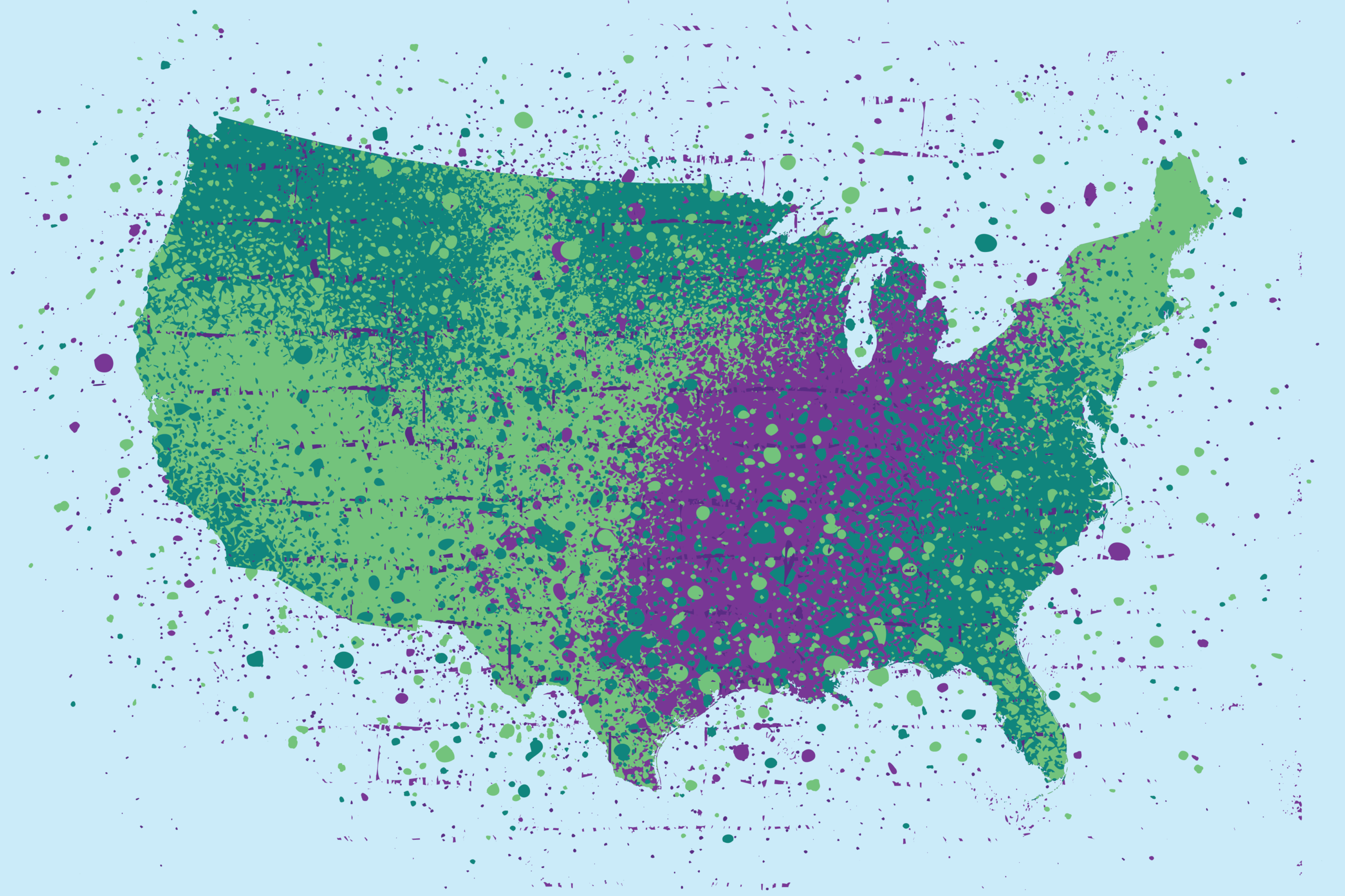

Zachary Metzger (Director, State of Local News Project, Northwestern University) provided a diagnosis of the national local-news collapse. The “ever widening gulf between the news haves and have nots,” he noted, is accelerating. 210 counties now have no local news source, and another 1,500 have only limited service. More than one-third of newspapers have disappeared, many of them small family-owned outlets that served as civic memory for their communities. The consequences are measurable: lower voter turnout, less transparency, higher corruption risk, and increased polarization as national news becomes a community’s only news source.

Public media, Metzger emphasized, remains one of the few institutions still physically present across these landscapes. “80% of news deserts can receive a public media signal,” and in states like New Hampshire, local public radio reporters have become essential civic infrastructure. Public media has both the technical footprint (repeaters, transmitters) and the reporting capacity to serve markets that commercial players have abandoned.

Systemwide Stability and the Post-CPB Financial Outlook

Tim Isgitt (CEO, Public Media Company) reinforced the scale of the challenge with new modeling. Public media generates $3.8B in revenue, with roughly $600M historically coming from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), a meaningful but not majority share. Without this stabilizing force, deep structural vulnerabilities are exposed: “cuts will fall disproportionately on rural and underserved communities,” and 43 million Americans could lose local service within a year without intervention. His team’s analysis indicates roughly half of all public media organizations are in distress, and “several stations are at risk of running out of money and going dark.”

In response, a coalition of funders, including the Knight Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation and the Ford Foundation, rapidly launched the Public Media Bridge Fund, a pooled fund aiming to stabilize at-risk stations and prevent a cascade of failures. With a goal of $100 million and more than $60 million committed, the fund is already processing 121 eligible stabilization applications, many from stations facing significant financial pressure. Its purpose is not to replace CPB, Isgitt stressed, but to buy time for stations to redesign themselves for long-term sustainability.

Policy and Regulatory Landscape

Steve Waldman (President, Rebuild Local News) described emerging state-level policy innovations: refundable employment tax credits for hiring reporters (Illinois, New York), government advertising set-asides, journalist fellowship programs, direct grants through independent state-funded nonprofits, and even consumer voucher proposals allowing residents to direct public dollars to news outlets of their choosing.

These diverse models suggest a broader evolution: ‘taxpayer supported media’ that works across platforms, not just broadcast. Yet Waldman also warned of volatility ahead, including challenges to noncommercial underwriting rules and revived scrutiny of editorial standards which could create new revenue vulnerability. His core point: “Number one market failure for public media: collapse of community news.”

Audience Behavior and Trust

Katerina Eva Matsa (Director, Pew Research Center) grounded the discussion in contemporary news consumption. “More than half of US users on X, TikTok, and Facebook get their news there,” she observed. Among adults under 30, trust in national news organizations and social media personalities is now roughly equal. About one in five Americans regularly gets news from influencers, with a much higher share among 18–29-year-olds. The appeal is not credentials but connection: individuals “help understanding of current events” and “feel authentic.” Young audiences increasingly expect journalists to be members of the community, not distant observers.

Funding for Local News

One major funder offered a candid assessment of the philanthropic landscape. They and their peers have supported a surge of experimentation across the country, yet “while there has been a lot of net new, we are not seeing a lot that is ‘cracking the code’” in terms of sustainable growth, audience reach, or diversified revenue. The sector has reached “that fork in the road,” this person said: continued fragmentation will not meet the scale of the crisis. The future requires bigger, more concentrated bets on organizations with clear specialization, such as the American Journalism Project, Public Media, Public Media Alliance, and Rebuild Local News, and a willingness to acknowledge when pilots are not delivering. Time, they emphasized, “is short.”

“Public media has good bones, but we need modernization.”

– Katherine Maher | President & CEO of NPR

The Role and Future of NPR

Katherine Maher (President & CEO, NPR) described a system rich in mission but in need of modernization. “Public media has good bones, but we need modernization.” Public media should be understood as public infrastructure, a civic asset with intrinsic and instrumental value. To align with contemporary needs, she argued for flipping the traditional structure: “Move from governance first to audience first.” She called for shared technology investment, better data, stronger digital interfaces, and deeper integration across the national-local network. Local libraries, she noted, have undergone transformations that offer instructive parallels for public media’s next chapter.

With the landscape established, the roundtable shifted into a series of deeper discussions examining what public media stands for, where it is falling short, and how it must evolve. These conversations revealed common principles, systematic challenges, and areas where bold redesign and reinvention are both necessary and overdue.

Discussion: The Values of Public Media

The group started by discussing why public media exists. Judy Woodruff (Senior Correspondent, PBS News) grounded the room in first principles: “Public media is an essential part of our democracy… If people don’t have access to information, how can they be a good citizen?” The work, she emphasized, is not about chasing “what’s going to bring more eyeballs,” but understanding “what Americans need to know” to be connected to their communities and to one another. Trust, she noted, remains one of public media’s most durable assets: “We are trusted. People do have that trust, that loyalty in public media.”

Ryan Merkley (Chief Operating Officer, NPR) added that public media’s value lies in its ability to create “connection to context… empathy – to be together in difference.” Warwick Sabin (President & CEO, Deep South Today) underscored the importance of credibility: in an era of polarization, public media must ensure its “editorial integrity” remains unimpeachable.

Jack Shiller (Graduate, Bennington College) captured the tension created by the media of today by paraphrasing E.O. Wilson’s adage: “We’re drowning in information, but starved for wisdom.” His point reinforced a recurring theme: public media’s value is not quantity, but clarity, grounding, and meaning.

Other participants emphasized public media’s emotional and relational value as a differentiator. Goli Sheikholeslami (CEO, POLITICO Media Group) said audiences often described their relationship with public media in deeply personal terms: “They felt they were in a relationship… a companion and a friend.” Trust, several noted, is built locally—through proximity, relationships, and accountability.

“Public media has failed to serve large elements of the public it was pledged to serve.”

– Silvia Rivera, Director of Local News at MacArthur Foundation

Participants also identified the tension between civic mission and economic incentives. Steve Waldman (President, Rebuild Local News) observed that public media’s financial model can create gravitational pulls toward well-educated, high-income donor bases—potentially misaligning the system with communities most in need of service. Silvia Rivera (Director, Local News, MacArthur Foundation) was more direct: “Public media has failed to serve large elements of the public it was pledged to serve.”

Many pointed to original reporting as the irreplaceable core. Sarabeth Berman (CEO, American Journalism Project) noted that while there are “plenty of synthesizers,” what communities lack is original, on-the-ground reporting. The trust gap—and the opportunity—is local.

The group identified these as shared values:

- Citizenship over consumption

- Trust and integrity

- Community connection

- Free access and openness

- Original, local reporting

- Service to historically underserved communities

These values, rather than platforms or legacy structures, surfaced repeatedly as the underlying foundation for what comes next.

Discussion: Gaps in the Marketplace

The discussion revolved around the needs public media is not currently meeting.

Melissa Bell (CEO, Chicago Public Media) was blunt: “What feels… completely broken is our distribution systems”—not content creation, but reach, relevance, and the ability to meet audiences where they already are. She argued that platforms optimized for outrage have taken over digital distribution, while too much of public media is still “building websites with updated designs” instead of understanding how people actually find information today. Audiences are on Facebook groups, WhatsApp threads, neighborhood forums, and other highly localized digital spaces.

Michael Giarrusso (Vice President – News Strategy, The Associated Press) pointed to AI-driven personalization as the next major shift. The challenge ahead is to “menu-ize the content of public media” and make it modular enough to be delivered in ways audiences actually use.

“Journalism is the only profession that tells the customer what they need in the way we decide to give it to them.”

– Amalie Nash, VP of Journalism at Knight Foundation

Several participants pointed to a mismatch between public media’s formats and what consumers expect. Amalie Nash (VP/Journalism, Knight Foundation) captured it starkly: “Journalism is the only profession that tells the customer what they need in the way we decide to give it to them.”

Waldman returned to the foundational issue: “The gap is not content, it’s reporting.” Public media’s competitive advantage is not newsletters or explainers, but accountability journalism. Carrie Lozano (President & CEO, ITVS) reinforced this: “You can have synthesizers and influencers, but the core of what we do is accountability journalism.”

Silvia Rivera (MacArthur Foundation) pushed the group to confront the equity implications: even before the collapse of commercial media, “large swaths of communities were not being served.” Without intentional redesign, public media risks rebuilding a system “for the elite again.”

Other participants saw the gaps as opportunities. Adam Blumenthal (Blue Wolf Capital) said: “If there is a gap, then that means someone wants it.” But Gary Knell sharpened the stakes: if public media simply doubles down on its existing donor-audience base, it will become “resistance radio”—narrower, more partisan, less civic.

Kenya Young (President & CEO, Louisville Public Media) made an important distinction: audience vs. community. Serving “audiences” can reinforce existing patterns; serving “communities” demands new approaches, new voices, and new definitions of who belongs in public media.

Discussion: Blank Slate

This session encouraged participants to imagine public media without legacy constraints.

Laura Walker (Bennington College) set the frame: “Take your uniforms off.” Apply public media’s core values to today’s environment—loneliness, declining trust, disconnected communities, AI reshaping information flows—and ask what system would best serve those needs.

Vilas Dhar (President, Patrick J. McGovern Foundation) focused on how AI could disrupt the system. With AI intermediating content, he asked, “What is a good version of [an] AI-intermediated world where our public media content reaches our audience?”

Michael Giarrusso (AP) argued that in an AI-driven environment, content must be “digestible” and modular.

But technology isn’t the only answer. Ryan Merkley (COO, NPR) emphasized relationships: “Technology always gets better, but… how do we get to that direct relationship and trusted relationship with audiences?”

Melissa Bell (Chicago Public Media) returned to the bedrock: public media’s “future relies on the connection we have with our communities.” She argued for rebuilding from local, local, local—and not giving up on the bond between communities and their reporters.

Participants also discussed structural constraints. Several said that current definitions of “public media” are outdated. Knell (BCG) said existing distinctions are “completely antiquated,” and that the system is not designed for emerging content forms like immersive media or data visualizations.

“We are the plankton… of this content food chain.”

– Steve Waldman of Rebuild Local News

Steve Waldman (Rebuild Local News) compared local reporters to ecological keystone species: “We are the plankton… of this content food chain.” Without local reporting as the raw material, everything downstream collapses. He also raised the example of libraries—publicly funded, community-rooted, and civically essential—as a model for reimagining public media.

Silvia Rivera (MacArthur) built on that idea: “What if we were modeled more like libraries… a community hub.” Tim Isgitt (Public Media Company) argued that the local stations—and the relationships they hold—are what must be preserved.

Goli Sheikholeslami (POLITICO) suggested that the system’s fundamental construct—especially the relationship between member stations and NPR—“needs to be completely blown up.” Stewart Vanderwilt (CEO, Colorado Public Radio) noted that the system has “too many entities trying to do too much with too few resources.”

Other participants focused on who gets to participate. Lolly Bowean (Ford Foundation) highlighted journalism’s long-standing gatekeeping structures: “We have become the gatekeepers of who becomes a reporter.” Future systems, she argued, should open the aperture to community information sources, including ethnic media and nontraditional contributors.

Katerina Eva Matsa (Pew) added that younger audiences already see journalists as community members and advocates, not necessarily credentialed elites.

Chi-hui Yang (Director, Creativity and Free Expression, Ford Foundation) asked participants to think about public media alongside libraries, museums, and civic institutions, asking: what information infrastructure does civil society require?

Discussion: What the Ecosystem Looks Like in the Future

This session challenged the group to consider what a reimagined system should look like.

Laura Walker (Bennington) asked the foundational question: “What do we need centralized organizations for?” Vivian Schiller (Aspen Digital) followed: “Where do we need institutional support?”

The national-vs-local tension came up again. Goli Sheikholeslami (POLITICO) said if she were rebuilding from scratch, she’d shift resources away from national and international coverage, which is abundant, toward local reporting, which is scarce. The system must re-examine whether its current structure is “set up in a way we can succeed in the future.”

Warwick Sabin (Deep South Today) described emerging statewide collaboration models in Arkansas, where local public radio stations, small newspapers, and growing regional outlets are centralizing infrastructure, sharing content, and building more unified statewide ecosystems. The results: greater efficiency, diverse content formats, and deeper collective reach.

Stewart Vanderwilt (CEO, Colorado Public Radio) warned of structural risks ahead: declining reliance on FM radio, vulnerabilities in underwriting revenue, and potential FCC rule changes that could “crush us very fast.”

Melissa Bell examined what stations get from being part of ‘public media’: CPB money, nonprofit tax advantages, and the halo effect of NPR’s brand. But she also noted the costs: high licensing fees and structural inconsistencies across the system. She argued that shared responsibilities and shared values could justify shared infrastructure, even if content remains decentralized.

“In 5 to 10 years, we need to know what lane we own.”

– Kenya Young of Louisville Public Media

Kenya Young (Louisville Public Media) raised a pressing question: “In 5 to 10 years, we need to know what lane we own.” For her, that lane is clearly local—to be the definitive source for local news in her community. But current capacity and funding constraints make it difficult to do it at the depth and scale required to truly be the newsroom of record for Louisville and Kentucky.

Tim Isgitt suggested that with CPB gone, the system may require a new centralizing force, one designed for the digital era rather than the broadcast era. Tom Glaisyer (Democracy Fund) agreed: the moment calls for “bold and audacious moves.”

Melissa Bell shared Chicago Public Media’s acquisition of the Chicago Sun-Times as an example of such boldness: an experiment in reaching new audiences, rebuilding trust, and reimagining local news at scale.

Katherine Maher (NPR) noted that national organizations provide brand, scale, and consistency—centralized advantages that could complement decentralized, community-rooted reporting.

Ryan Merkley (NPR) added that leadership in a network doesn’t require ownership—it requires shared data, shared platforms, and collaborative technology, especially as AI reshapes the information ecosystem.

Next Steps

Four themes emerged about the work ahead—not as recommendations, but as what participants said was necessary.

- Relationships and Trust: Celeste Ford (Chief Communications Officer, Carnegie Corporation of New York) emphasized the need to “lean into relationships” with communities, with funders, and across organizations. Kyle McEneaney (Director, The Schmidt Family Foundation) said news may need to be treated as a loss leader, with public media exploring more creative, diversified revenue strategies that align with mission and sustainability.

- Sustainable Economic Architecture: McEneaney underscored the danger of “throwing good money at a system that doesn’t work,” pushing the group to identify pilots that can scale—like the Deep South model—and to foreground these for funders. Participants agreed that the system’s economic fragility can’t be ignored; a new structure is essential. Several noted that the legacy national institutions such as PBS and NPR must rapidly evolve the services they provide, from traditional broadcast-era functions towards shared digital infrastructure, audience insight and technology capabilities. As Katherine Maher (NPR) noted, public media capital investment “does not reflect the adoption and opportunities of digital.”

- Innovation and Experimentation: Vilas Dhar (McGovern Foundation) pointedly asked how much public media invests in innovation compared to legacy operations. Tom Glaisyer (Democracy Fund) asked how to build a people’s constituency for public media—one rooted in civic participation rather than institutional loyalty.

- Long-Term Roadmap and Stewardship: Chi-hui Yang (Ford Foundation) articulated the need for a 10-year roadmap, designed intentionally and stewarded by an entity empowered to carry the work forward. “There needs to be somebody that’s tasked with doing this – a commission maybe.”

End-of-Day Reflection

Co-hosts Vivian Schiller (Aspen), Gary Knell (BCG) and Laura Walker (Bennington) gave a candid assessment to close the day. They agreed the system needs a blueprint: a shared definition of what public media is and should become. Without such clarity, Knell warned, the sector risks devolving into a “Hunger Games in public media,” competing for shrinking resources rather than building a cohesive future.

The convening didn’t produce prescriptions, but rather key principles:

- Public media’s mission is more essential than ever.

- Its structures are misaligned with the world it must now serve.

- Its value lies in trust, proximity, and local reporting.

- Its future depends on redesign, not restoration.

The work ahead is substantial. But the day’s candor, urgency, and shared recognition of both risk and opportunity provided a strong foundation for imagining what comes next.

We are grateful to the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation, along with the Ford Foundation, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York for their support.