Executive Summary

The purpose of the Community-Aligned AI Benchmarks initiative is to help communities better articulate their needs and aspirations to technology researchers and builders to ensure that AI systems are designed to meet public priorities. Aspen Digital chose SDG 2: Zero Hunger as an under-explored pilot issue area and then ran a global survey designed to understand the most significant challenges facing food security and to identify the strategies experts consider most effective to address them. The findings represent perspectives from over 100 participants from around the world with experience in nutrition, policy advocacy, education, entrepreneurship, and philanthropy representing work in 20 out of the 22 United Nations (UN) Statistical Division geographical regions.

Food security is a pressing global challenge that has only become more urgent in the last year, with an estimated 2.3 billion people facing moderate or severe food insecurity, and many countries dramatically decreasing their commitments to international aid. Unfortunately, existing efforts to explicitly align AI research with food security priorities remain limited—only 3.6% of AI-for-SDG projects address the ‘Zero Hunger’ goal despite its global importance. Most AI for food security projects focus on food production, but our survey results reveal that many of the breakthroughs that could unlock substantial progress on world hunger and malnutrition may intervene on other aspects of food security. While Production and Resource Management is a high-priority challenge, survey participants converged around two related governance-focused strategies.

The highest priority course of action based on these findings is: Strengthen transparency, accountability, and participatory decision-making, especially in government food system administration and land governance.

Background

World hunger remains a persistent issue facing humanity with between 638 and 720 million people undernourished and 2.3 billion experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity in 2024. While the challenges to achieve a sustainable food-secure future are significant, there are many deeply knowledgeable people around the world who are both rooted in impacted communities and are dedicated to making progress.

In the last decade, a series of technological breakthroughs in AI have opened new possibilities to empower these change-makers and drive real progress towards food security. To realize this potential, we must bring together tech innovation with on-the-ground wisdom to maximize impact. With Community-Aligned AI Benchmarks, Aspen Digital is developing more impactful ways for communities to articulate their needs and aspirations so that technology researchers and builders can focus where it matters most.

Prior Work

Aspen Digital reviewed academic studies and reports from leading international organizations to establish a solid conceptual and empirical foundation for the survey. In addition to this desk research, we organized dozens of expert interviews, a multi-stakeholder workshop series, and a public webinar to capture diverse perspectives from more than 35 practitioners and researchers.

Our earlier publication, Intelligence in the Public Interest, mapped how AI research and funding remain concentrated in areas often disconnected from the urgent development priorities across the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). From June of 2025 through January 2026, only 3.6% of the projects tracked by the AI for SDGs Think Tank address the ‘Zero Hunger’ goal despite its global importance. Reclaiming AI for Development serves as a complementary report, reinforcing the need to design smarter benchmarks—metrics that align technological progress with development priorities and the lived realities of local communities. This analytical groundwork informed the survey’s design and focus on strengthening food systems.

What’s the Tech Angle?

Readers of these findings may say to themselves, “this is all very interesting, but why is Aspen Digital leading an initiative around food security?” After all, the Feeding the Future survey did not ask food security practitioners about AI technologies or how they might show up in their work. In fact, in the workshops and survey we intentionally avoided discussions of technology interventions (for more details, see Annex B: Survey Language).

Too often, discussions of “social impact technology” or “AI for good” start with the tools. They ask, “where can these capabilities be applied?” rather than “what capabilities are needed?” Community-Aligned AI Benchmarks challenges this notion: it starts with the people working on the ground and asks what they need to be successful. Taking this approach avoids coloring the discussion with preconceived notions about what is easy or even currently possible. Rather than limiting our scope to the technologies that are available or the tools that food security experts are aware of, we explore where the highest-impact solutions should focus and what capabilities are needed to drive real change.

We do believe that technology will be essential to making much-needed progress on important social impact challenges, like food security. But to do the most good, we must center people—not AI—in our process.

In the next stage of this work, Aspen Digital is bringing together food security practitioners with technology experts to create a new AI research agenda that centers social impact. We invite you to join us!

Survey Design

The Feeding the Future survey ran from July through September 2025 and was available in four languages—English, Spanish, French, and Chinese—to increase global accessibility and inclusion. The anonymous survey was structured into three sections: a challenge-ranking section, a strategy-ranking section, and a demographics section. For more details about methodology, see Annex A: More Detailed Methodology.

In total, 115 participants ranked six challenges from most to least pressing and 98 ranked a random subset of 53 strategies for two of the challenges. Optional demographic questions revealed that many participants had significant experience in the field (31 of the 82 who answered have more than 10 years of experience) and most have expertise in policy and governance (49 people), climate change and environmental sustainability (41 people), and traditional food systems and community-based initiatives (35 people). Participants work at NGOs or civil society organizations (23 people), in academia (18 people), the private sector (10 people), or international organizations (8 people).

The geographic focus of participants’ work was also quite diverse. The survey asked participants which geographical regions defined by the UN Statistical Division were the primary focus of their work. (Participants could select more than one.) Twenty out of the 22 subregions were represented. Despite efforts made to ensure diversity and inclusiveness—through multilingual distribution and regional partnerships—the composition of respondents nonetheless reflects institutional and geographic bias towards North America.

To counterbalance this bias, we weighted responses proportionate to the number of food insecure people living in the regions where participants’ work is focused to better represent the challenges and strategies that would have the greatest impact on the greatest number of people. To achieve this, we clustered responses by development (according to the UN’s Human Development Index, or HDI) into three clusters:

- Less Developed Regions: Western Africa, Eastern Africa, Middle Africa, Melanesia, Southern Asia, Southern Africa, Micronesia, & Northern Africa (average HDI: 0.60)

- More Developed Regions: Polynesia, Eastern Asia, Central America, South-eastern Asia, Central Asia, Caribbean, South America, & Western Asia (average HDI: 0.76)

- Most Developed Regions: Western Europe, Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, Northern Europe, Northern America, & Australia and New Zealand (average HDI: 0.88)

Because selecting regions of work was an optional question, some survey participants were categorized as No Regions Selected. 35% of responses (representing 40 participants) were in this cluster.

These clusters are similar to, but not the same as, the UN Development Programme HDI categories, which are determined at the country level. Because these regions contain multiple countries with different HDI levels, we averaged the HDI value of the constituent countries to produce a regional HDI score and then developed the clusters by grouping similar regions into three similarly sized groups. These clusters allow us to break down analysis in order to reveal the different priorities of people working in regions of lesser and greater development.

Top Challenges by Region

In the first part of the survey, 115 participants ranked six key challenges spanning the food security landscape which we sourced from workshops with experts and landscape research:

- Production and Resource Management: Challenges related to low yields, limited access to inputs, and poor management of natural resources

- Access and Distribution: Barriers to transporting, marketing, or delivering food

- Nutrition and Food Utilization: Issues affecting the ability to access, prepare, or consume safe and nutritious food (including knowledge and hygiene gaps)

- Institutional Capacity and Governance: Weaknesses in coordination, regulation, implementation, or monitoring by public or community institutions

- Finance and Risk Management: Limited access to financial services to expand capacity or manage economic and climate-related shocks

- Labor, Equity, and Inclusion: Structural inequalities limiting access to land, resources, and opportunities for women, youth, and marginalized groups

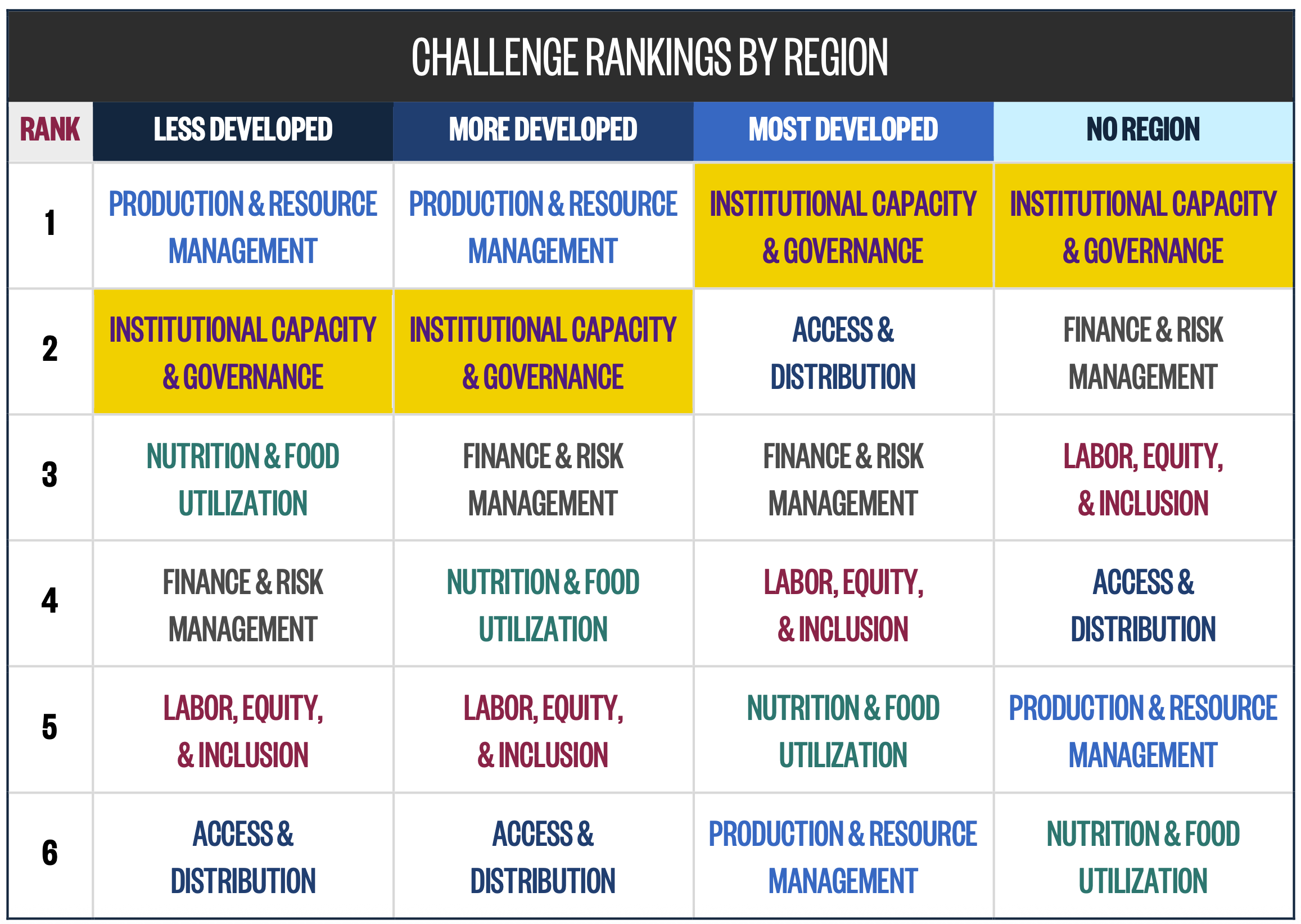

Institutional Capacity and Governance was a top-ranked challenge across all responses, coming in first or second place across all clusters. When we break those results down by region, we see that participants in the Less Developed Regions and More Developed Regions clusters prioritize Production and Resource Management and minimize Access and Distribution, whereas that flips for Most Developed Regions. Finance and Risk Management is ranked moderately across all clusters, while Nutrition and Food Utilization is prioritized more highly in Less Developed Regions.

We weighted selected strategies in the next part of the survey based on how each cluster of participants prioritized the six challenges so that strategies for highly rated challenges were given greater weight.

Top Strategies Overall

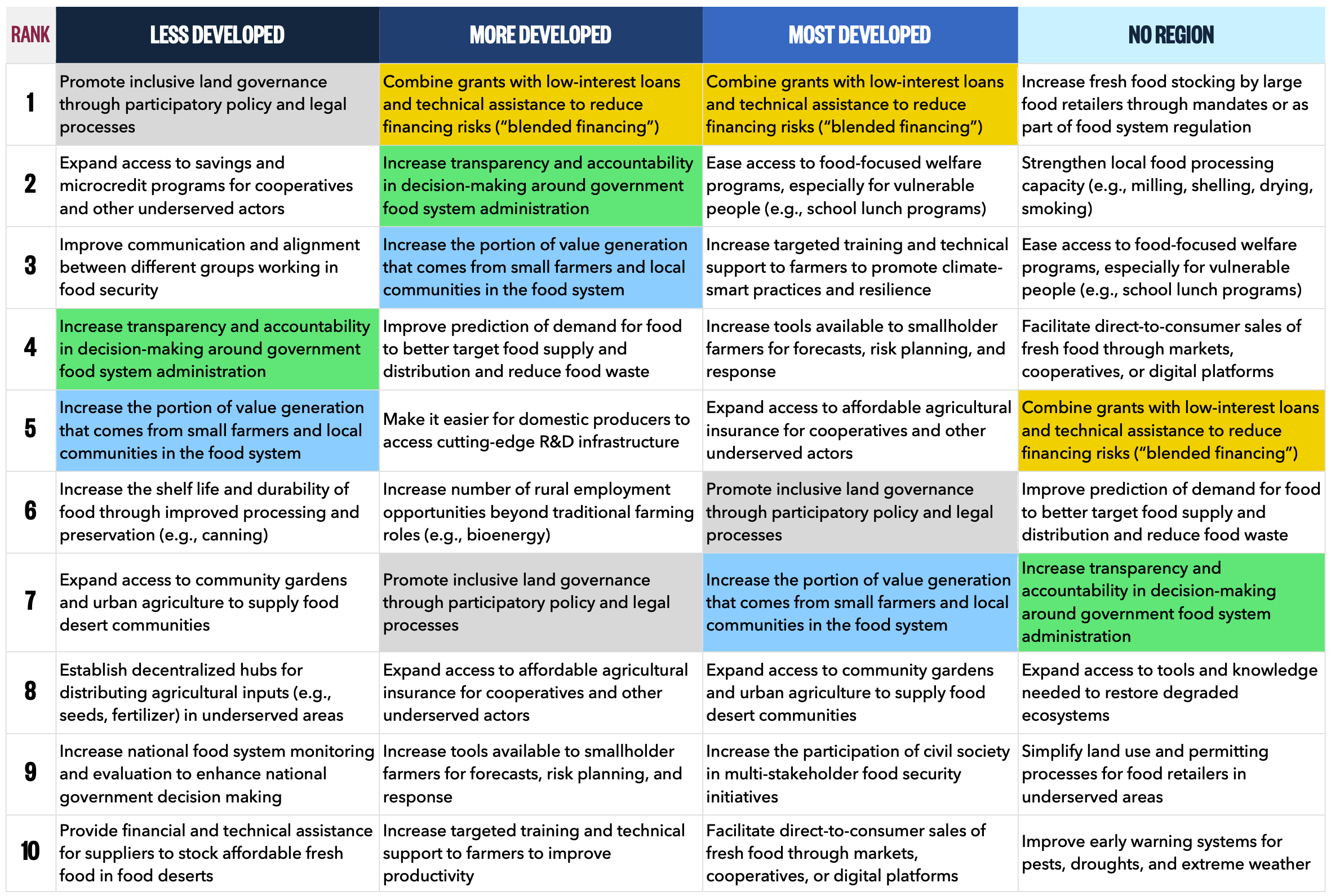

Our analysis focuses on the top cross-cutting strategies, meaning those that were ranked highly across many different challenges. We believe these strategies will have the highest potential impact if implemented due to their ability to “unlock progress” across several important issues in food security. See Annex C: Ranked Strategy List for the full ranked list of 53 strategies.

Ninety-eight participants chose which one of four randomly selected strategies would best address a particular challenge. To identify cross-cutting strategies, we sum the score for each strategy from the four development region clusters, weighted according to food security need and challenge rankings (see Table 1), and take the highest results.

The top five overall strategies are:

- Promote inclusive land governance through participatory policy and legal processes

- Increase transparency and accountability in decision-making around government food system administration

- Expand access to savings and microcredit programs for cooperatives and other underserved actors

- Increase the portion of value generation that comes from small farmers and local communities in the food system

- Combine grants with low-interest loans and technical assistance to reduce financing risks (“blended financing”)

These strategies emphasize governance and financial inclusion. We believe this is because those strategy types are most cross-cutting for our particular set of challenges, while other strategies participants highlighted were more specific to individual challenges. For example, #1 above was ranked in the top ten strategies for three of the six challenges: Access and Distribution, Institutional Capacity and Governance, and Finance and Risk Management, while a strategy focused on drip irrigation only ranked highly for one challenge: Production and Resource Management. All of the top overall strategies were in the top ten strategies for multiple food security challenges. For deep dives into the top strategies for each of the six challenges, see our Challenge Spotlights.

Because the two top overall strategies focus on similar aspects of governance, we merged them into the following strategy. Based on our survey results, this is a strategy which, if realized, has high potential impact to substantially accelerate food security:

Strengthen transparency, accountability, and participatory decision-making, especially in government food system administration and land governance.

Bottom Overall Strategies

While the top strategies are our primary focus, it can also be illuminating to see which strategies were selected least. These five strategies were selected fewer than 50 times, despite collectively being presented as options more than 380 times.

- Improve accuracy of financial fraud detection to lower risks and encourage more investment

- Reduce the cost of transporting food through greater vehicle fuel efficiency or reduced maintenance costs

- Increase tools available for government enforcement of current regulations

- Increase transparency and accountability in decision-making around international food aid programs

- Increase public awareness of the harms and negative impacts of less nutritious food

What is notable about these least popular options is that they echo strategies that were chosen most frequently. While highly ranked options tend to emphasize governance and transparency at the level of individual governments, lower-ranked strategies suggest that the integrity of the international food aid system and financial risk detection mechanisms is not widely perceived as a core problem. Similarly, there is noticeably less interest in strengthening enforcement of existing regulations, which may reflect a shared view that current failures lie more in how systems are designed or governed than in weak application of the rules themselves. A further contrast appears in nutrition strategies: positive, benefit-focused awareness campaigns were favored over those emphasizing negative consequences of unhealthy food, which aligns with existing evidence that positive framing is often more effective for behavior change.

Results by Level of Development

In addition to challenge-based analysis in the Challenge Spotlights, here we look at region-based results to explore how participants from different clusters prioritize strategies. In Table 2, there are four shared strategies across three of the four participant clusters. Two strategies—promoting inclusive land governance and strengthening transparency and accountability in government food system administration—tie the local to the institutional, ensuring that communities have both a voice and a stake in decision-making. Another shared strategy, increasing the portion of value generation from small farmers, focuses on small-scale actor empowerment. A final shared strategy, reducing financing risks via blended financing, reflects a recognition that strategically combining diverse sources of capital can lower effective financing constraints and enable the participation of actors who would otherwise be unable to enter formal financial markets. Taken together, these four recurring strategies paint a picture for resilient food systems where equitable governance, bottom-up value creation, and financial inclusion reinforce one another.

Less Developed Regions emphasize strategies that strengthen food systems infrastructure

In Less Developed Regions, participants’ top strategies reflect a deep concern for inclusion and basic system foundations. The highest-ranked priorities—promoting inclusive land governance, expanding access to microcredit and savings programs, and improving communication among actors in food systems—signal an effort to address structural gaps that often exclude small producers and local communities from the benefits of modernization. Complementary measures such as enhancing national monitoring systems, increasing food durability through preservation methods, and establishing decentralized hubs for distributing agricultural inputs focus on building the institutional and productive infrastructure necessary for food systems to function, starting from the ground up.

More Developed Regions emphasize strategies that focus on stability and efficiency in food systems

In More Developed Regions, participants prioritized strategies to promote consolidation and efficiency, such as by stabilizing production while gradually integrating more advanced instruments for risk management and innovation. Similarly to Less Developed Regions, the prioritized strategies include increased transparency in government food system administration, but this cluster adds on additional forms of coordination, such as improving demand prediction, reducing waste, and expanding agricultural insurance. Prospects for small farmers remain a priority, but there is greater emphasis on facilitating access to innovation infrastructure, including R&D centers and rural employment diversification. This mix of strategies suggests a focus less on basic access and more on fine-tuning policies that connect financial access and institutional mechanisms with upgraded technologies, marking a transition from subsistence toward competitiveness.

Most Developed Regions emphasize strategies that democratize and future-proof access to food

In the Most Developed Regions, participants emphasize strategies that improve access to nutritious food and increase the food system’s climate resilience, which is also reflected in this cluster’s uniquely high prioritization of the Access and Distribution challenge. Strategies for increasing access include direct-to-consumer sales of fresh food, food-focused welfare programs like school lunch programs, and local food production like community gardens. Unlike other regions, this cluster more directly prioritizes strategies that make the food system more resilient in the face of climate change. In these regions, access disparities and governance challenges take precedence over foundational production infrastructure.

Participants who did not provide demographic information reflect a mix of the above three regions, albeit with a focus on increasing fresh food supply through smarter regulations as their collective top pick.

While we were thrilled to have participation from a diverse global community of practitioners and experts for this survey, we recognize that many perspectives were not represented. We welcome additional communities to add their voices and share their priorities and perspectives. If you are interested in replicating this survey methodology in your own community, please reach out to us. We’re happy to share resources and learnings!

Annexes

Dive Deeper with Challenge Spotlights

Acknowledgements

This work was produced by Francisco Jure, Eleanor Tursman, and B Cavello, and was made possible thanks to generous support from Siegel Family Endowment.

Many thanks to Kyle Newell, Shanthi Bolla, and Brandon Jackson for their invaluable thought partnership and to Rob Lach and Community Priority for developing our survey.

We would also like to thank Vanessa Adams, Rachel Atcheson, Irene Arias Hofman, Robert Egger, and Eugenia Saini, Tess Geers, Shungu Kanyemba, Kalpana Khanal, Kyriacos Koupparis, David Laborde, Chris Lewis, Mohammed Mofizur Rahman, Bedan Mukoma, Elias Mulhall, Mandla Nkomo, Gadha Raj, Christian Resch, Glen Surnamer, Salvador Urrutia Loucel, Balaji Vasudevan, and Patrick Webb for helping shape this work.

We’re also grateful to the following people who helped us connect with food security practitioners around the world: Anissa Arakal, Davar Ardalan, Dinesh Balam, Adam Burk, Toby Cain, Alejandra Ceja, Hakeem “Chef Hak” Otenigbagbe, Catherine Compitello, Indivar Dutta-Gupta, Annalies Goger, Jimmy Jaramuzchett, Jeffrey Kahn, Sarah Kalloch, Chenai Kandungure, Athina Kanioura, Martha Kuria, Benjamin Kwasi Addom, Nino Lazariia, Gisèle Yasmeen, Matthew Licina, Miriam Lueck Avery, Clarence Mashavave, Latifa Mbarak, Hope Michelson, Lourdes Montenegro, Craig Newmark, Marielle Olentine, Jennifer Peacock, Megan Roberts, Jonathan Roberts, Gonzalo Rondinone, Carmen Ruiz, Aditi Rukhaiyar, Pablo Russo, Jenna Slotin, Tara Sprickerhoff, Dan Taber, Jessica Tangelder, Laura Tarre, Rachel West, and Annie Yaqin Zhou.

Thank you to everyone who contributed perspectives to this initiative. We could not do this without you.