This spotlight presents the top strategies for improving nutrition and food utilization, including addressing issues affecting the ability to access, prepare, or consume safe and nutritious food (including knowledge and hygiene gaps).

These findings represent survey input from 98 participants working in food security across 20 of the 22 UN Statistical Division geographical regions. In the Regional Breakdown of Results section, responses are grouped into three clusters by Human Development Index (HDI) based on the geographies of participants’ work: Less Developed Regions, More Developed Regions, or Most Developed Regions. For more information on our methodology and the full list of challenges and strategies, see the Feeding the Future main report.

Nutrition sits at the foundation of human development. It shapes health, cognitive growth, productivity and ultimately the social and economic trajectory of entire communities. Historically, societies were organized around the search for food and water, and technological change later transformed that landscape by enabling surpluses, long-distance transport, and new forms of distribution. Yet these advances also introduced new challenges. Many modern diets rely heavily on ultra-processed foods or fail to deliver essential nutrients, even in high-income settings where food insecurity is lower but nutrition remains a key determinant of wellbeing. In more vulnerable regions, where every calorie and micronutrient carries weight, the strategic composition of diets can determine not just quality of life but survival itself.

Overall Top Strategies for Nutrition & Food Utilization

#1 Expand access to community gardens and urban agriculture to supply food desert communities

This strategy combines two elements: proximity-based production and improvements in the quality of food reaching the most underserved communities. Creating community gardens and promoting urban agriculture shortens the distance between food production and local communities. Food doesn’t need to be consumed closer to its origin to be more nutritious, but a series of processes and infrastructure, such as refrigeration, effective post-harvest handling, storage and transport systems, must be in place in order to preserve nutritional value—conditions often absent in communities far from urban centers or in low-development settings. Especially in low development contexts, expanding local and community-based production can become a key alternative, especially for minimally processed products.

#2 Provide financial and technical assistance for suppliers to stock affordable fresh food in food deserts

Storage conditions can make the difference between healthy food and food that loses essential nutrients—or even becomes unsafe. In that sense, this strategy builds capacity among suppliers by providing tools that expand their ability to stock fresh food, especially in food deserts. By improving cold-chain reliability and basic storage infrastructure, it helps stabilize supply in places where disruptions are frequent and options are limited, ultimately reducing vulnerability for communities that already face the highest barriers to nutritious food.

#3 Ease access to food-focused welfare programs, especially for vulnerable people (e.g., school lunch programs)

The third most selected strategy includes a set of measures aimed at lowering access barriers for people whose inconsistent income threatens their food security. The mechanism for this strategy can take multiple institutional forms: food transfers (such as India’s Public Distribution System, focused on providing affordable grains), vouchers (like WFP e-vouchers, a flagship digital model for Syrian refugee families, among others), cash transfers for food (such as SNAP, formerly Food Stamps, in the United States), and school feeding programs (such as Brazil’s National School Feeding Program, which reaches 44 million students per year). These types of programs have proven effective worldwide in reducing extreme poverty and ensuring access to a basic food basket. Persistent challenges remain, however, including program access difficulties due to strenuous requirements, challenges correctly identifying target populations, or encouraging the selection of healthier food.

#4 Improve communication and alignment between different groups working in food security

Nutrition depends not only on access to quality food but also on the ability to establish and sustain healthy eating habits. Multiple strategies can contribute to this goal, but coordination among actors working at strategic, programmatic, and territorial levels is essential to support these processes and enhance the effectiveness of other interventions. In vulnerable or geographically excluded populations, a multi-actor approach becomes a critical catalyst for effective food assistance. Recognizing this importance, some strategies already focus explicitly on multi-actor coordination. For example, Timor-Leste’s National Multisector Nutrition Action Plan brings together health, agriculture, education, and local authorities under a shared framework, aligning actions across strategic and programmatic levels to improve nutrition outcomes, particularly for vulnerable populations.

#5 Increase the portion of value generation that comes from small farmers and local communities in the food system

Small family farmers produce roughly one third of the world’s food, underscoring their central role in supplying diverse and nutritious diets. When these producers are supported with access to land, inputs, finance, and local markets, they are better able to meet their own nutritional needs and generate surplus food for nearby communities. This kind of empowerment shifts food systems away from long and fragile supply chains toward local circulation of value. Over time, enabling small farmers to produce and sell nutritious food locally can reduce dependency on external supply, develop greater efficiencies locally, and improve nutrition outcomes at the community level.

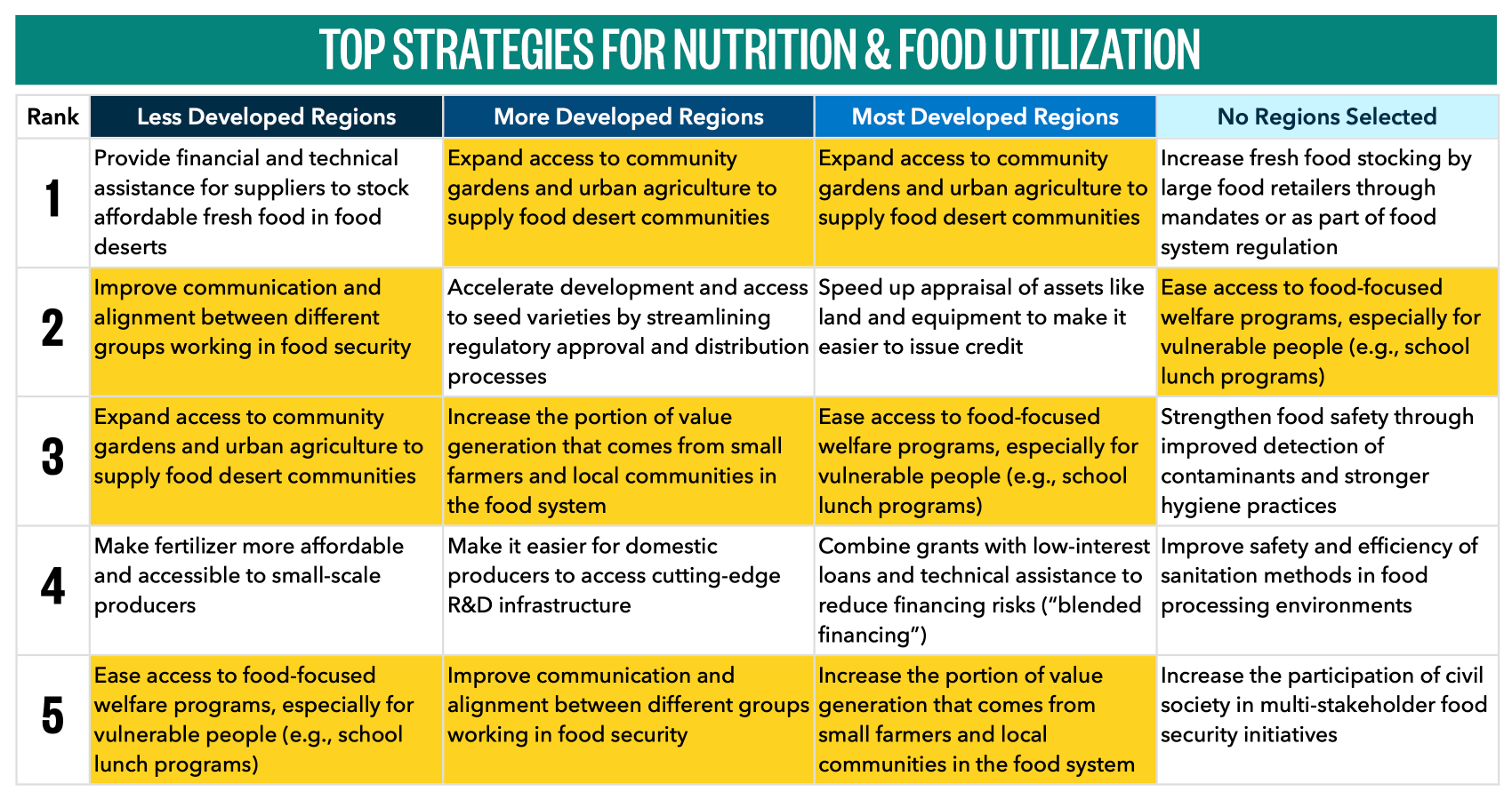

Regional Breakdown of Results

Although there was overlap between preferred strategies across the different region clusters, Nutrition and Food Utilization exhibited less overlap than most of the other high-level challenges in food security. While there were several shared top strategies amongst participants who shared information about their region of work, the No Regions Selected cluster stands apart. That cluster, in particular, placed greater emphasis on food safety. Additionally, the top strategy—Increase fresh food stocking by large food retailers through mandates or as part of food system regulation—for the No Regions Selected cluster was also a bottom five strategy for participants representing Less Developed Regions and Most Developed Regions.

The top five and bottom five strategies for improving Nutrition and Food Utilization, clustered by region development level. The “no regions selected” category covers participants who did not enter demographic information in the survey. White cells are unique (only appear in one region) and colored cells are shared by two or more regions. For more information on clustering, see Annex A: More Detailed Methodology.