This spotlight presents the top strategies for improving institutional capacity and governance, including addressing weaknesses in coordination, regulation, implementation, or monitoring by public or community institutions.

These findings represent survey input from 98 participants working in food security across 20 of the 22 UN Statistical Division geographical regions. In the Regional Breakdown of Results section, responses are grouped into three clusters by Human Development Index (HDI) based on the geographies of participants’ work: Less Developed Regions, More Developed Regions, or Most Developed Regions. For more information on our methodology and the full list of challenges and strategies, see the Feeding the Future main report.

Development studies practitioners have spent decades trying to understand the forces that enable better living conditions. One conclusion has become hard to ignore: institutions matter. In 2024, Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson received the Nobel Prize in Economics for showing that a country’s prosperity hinges on the quality of its institutions. Societies marked by weak rule of law or extractive arrangements often struggle to generate lasting growth. In food systems, the same logic holds. Institutions shape the incentives and constraints that determine how actors operate, from what crops they grow to the kinds of innovations they pursue.

Technology sits at the center of this institutional landscape. It thrives in inclusive environments that enable experimentation and efficient resource allocation. But it can also reshape institutions themselves. Depending on how it is deployed, technology can broaden participation and accountability or concentrate economic and political power in ways that weaken governance. Today’s tools such as AI-enabled monitoring, digital identity systems, and traceability platforms, capture this duality clearly. They can democratize access and strengthen resilience, or, if poorly governed, reinforce existing inequalities.

Overall Top Strategies for Institutional Capacity & Governance

#1 Promote inclusive land governance through participatory policy and legal processes

Land governance is a central issue, especially in Less Developed Regions and More Developed Regions. There is robust evidence showing that clarifying property rights acts provides a strong incentive to improve productivity and stewardship of plots. At the same time, policies grounded in participatory processes tend to achieve greater acceptance, more inclusive design, and higher effectiveness in improving community wellbeing. Inclusive governance ensures that local knowledge and historical experiences shape the rules that ultimately determine access and equity, strengthening the overall food system’s institutional capacity.

#2 Improve market access and reduce delivery delays by rehabilitating and upgrading transportation infrastructure

Where institutions are fragile—potentially due to unclear regulations or corruption—transportation infrastructure projects tend to be delayed or overrun costs. By contrast, where governance is stronger, investments lead to greater access to regional markets and a more stable food supply chain. As such, it is logical that professionals who view infrastructure upgrades as a high-impact strategy would also regard institutional capacity and governance as fundamental bottlenecks in the sector. Transportation upgrades generate sustainable benefits only when there is institutional capacity to coordinate investment, maintain infrastructure, regulate use, and ensure that improvements translate into expanded market access for small producers. At the same time, improvements in transport infrastructure foster participation in broader and more transparent markets which ultimately strengthen institutional quality.

#3 Increase transparency and accountability in decision-making around government food system administration

Transparency plays a central role in food system governance, where public decisions shape the allocation of scarce resources such as subsidies and emergency food reserves. In the absence of clear and accessible information, food systems are especially vulnerable to capture by economic or political actors with enough influence to extract rents or shape policies to their advantage. Accountability therefore becomes an essential complement: transparency alone does not prevent distortions unless institutions are able to assign responsibility for policy choices and enforce compliance. Together, transparency and accountability act as safeguards against distortions that weaken food systems and undermine equitable access to food.

#4 Increase national food system monitoring and evaluation to enhance national government decision making

Effective food system monitoring reshapes government action by making vulnerability visible while it is still unfolding. When governments track key dimensions in near real time, food insecurity becomes a signal to act rather than a lagging indicator. Systems such as FEWS NET, which combines climate, market, and livelihood data to anticipate food crises, and the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, which classifies the severity of food insecurity to guide policy responses, have been used by governments to expand cash transfers and adjust trade policies ahead of shocks. Their value lies in shortening the distance between evidence and decision-making, allowing policymakers to move early and decisively instead of responding once damage is already done.

#5 Expand access to savings and microcredit programs for cooperatives and other underserved actors

Institutional capacity and the depth and stability of financial markets are strongly correlated. The relationship is not one-to-one, but decades of research in institutional economics and development finance have consistently shown a link, while institutional weakness is associated with smaller and more volatile markets. In other words, one way to expand credit access for underserved actors is to strengthen institutions. A clear example is Brazil, where the reinforcement of public guarantee funds enabled agricultural cooperatives and small producers to access credit lines that had previously been out of reach, reducing the perceived risk for banks. A similar dynamic occurred in India with the rollout of Aadhaar, which professionalized identity verification processes and allowed millions of informal actors to enter the formal financial system, opening the door to microcredit and productive loans.

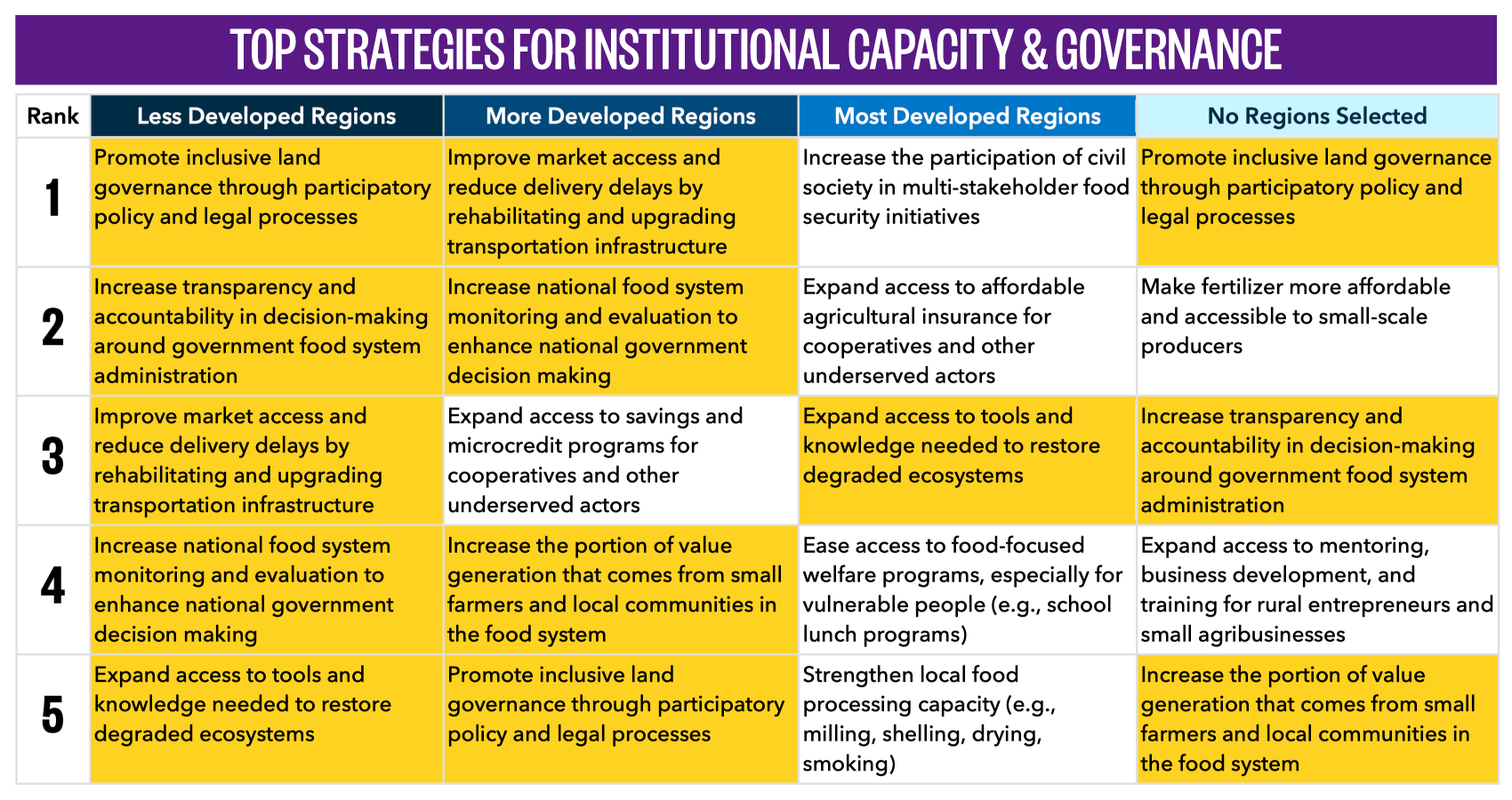

Regional Breakdown of Results

Compared to other food security challenges, Institutional Capacity and Governance shows the starkest difference in answers between Most Developed Regions and the other clusters. This reflects the relationship between development level and institutional capacity. Many of the preferred strategies focus on increasing access and accountability to traditionally marginalized actors. Interestingly, even though access to finance was prioritized across participants in both Less Developed Regions and More Developed Regions, improving fraud detection to lower investment risk was rejected as a strategy in these same regions. Similarly, Increase tools available for government enforcement of current regulations was not in the top strategies for any development region cluster (and ranked 17th for this challenge overall).

The top five and bottom five strategies for improving Institutional Capacity and Governance, clustered by region development level. The “no regions selected” category covers participants who did not enter demographic information in the survey. White cells are unique (only appear in one region) and colored cells are shared by two or more regions. For more information on clustering, see Annex A: More Detailed Methodology.