How to use this guide

This policy primer provides a clear and accessible foundation for understanding how artificial intelligence is evaluated through benchmarks. Its goal is to equip journalists, educators, policymakers, and other members of the public with the knowledge to interpret AI performance claims critically and use this understanding to inform effective governance.

For a list of resources on where to find technical experts, please see Finding Experts in AI. For information specifically on generative AI, please see our accompanying guide Intro to Generative AI. For information on AI more generally, please see AI 101. Visit Emerging Tech Primers to see all primers.

What is an AI benchmark?

AI benchmarks are a type of standardized test that AI researchers and builders use to measure the performance of their AI systems. Just like there are many different types of standardized tests, there are many different benchmarks that measure different things. AI benchmarks are typically composed of two datasets representing AI prompts and expected “answers.”

People use AI benchmarks to compare how different AI models perform on particular tasks such as:

- Detecting Breast Cancer: The medical imagery and analysis in the MAMA-MIA challenge were developed specifically for AI researchers to test their AI models for performance on both labeling cancer in MRI imagery and predicting the response to treatment.

- Solving Math Problems: Some benchmarks are based on exams and tests created for people. The MATH dataset is a collection of math questions and answers compiled from past high school math competitions.

- Broad Question Answering: The designers of Humanity’s Last Exam crowdsourced a collection of graduate school-level questions and answers from a variety of disciplines in response to concerns that AI benchmarks have not been sufficiently challenging and diverse.

Why benchmarks matter

Benchmarks shape the AI development ecosystem. They provide structure and increase the rigor of research through standardized comparisons. Additionally, benchmarks work as performance targets to chase (like how educators might “teach to the test”).

Popular benchmarks can influence the type of research that gets funded, what research is published, and what types of projects are pursued. For example, medical researchers created a benchmark to improve modeling of protein structures, inspiring the creation of AlphaFold, an AI system that dramatically increased capabilities and has since been made open source.

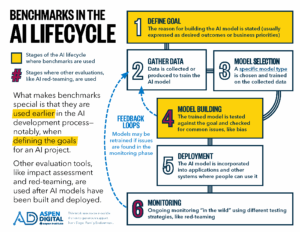

Benchmarks are not the only way that people measure AI systems. At different stages of AI development, different types of monitoring and evaluation can be used. What makes benchmarks special is that they are used earlier in the AI development process—notably, when defining the goals for an AI project. Other evaluation tools, like impact assessment and red-teaming, are used after AI models have been built and deployed.

One critique of benchmarks is that they measure performance “in the lab” instead of “in the wild.” While this is true, compared to other types of evaluation, benchmarks are relatively fast and easy for AI researchers and builders to use, which means that fixes can be incorporated more quickly.

We need a mix of different AI evaluation practices to capture the full impact of AI.

What makes benchmarks special is that they are used earlier in the AI development process, when defining the goals for a project.

How to interpret a benchmark

Like other “standardized tests,” benchmarks are useful, but imperfect. It’s important to understand what a benchmark actually measures before extrapolating about what it means.

What capabilities does the benchmark measure?

Benchmarks cannot test for all things, so it’s important to understand what specific capabilities or tasks a benchmark is designed to measure. Just as measuring the color of a flower doesn’t capture the whole experience of a flower (like its smell, role in the ecosystem, or taxonomy), the metrics measured with a benchmark may only capture one dimension of a job, ability, or action.

To figure out what in particular a benchmark measures, it can help to look at the specific sample problems and solutions provided in the benchmark. For example, two different benchmarks may have been designed for chemistry applications, but one might measure predictions of chemical models whereas another might be a questionnaire about lab safety.

It can be tempting to overestimate what an AI system can do, especially because benchmark scores often show AI models outperforming a human baseline. But benchmarks only measure specific, narrow tasks. A calculator is effective at arithmetic, but this doesn’t mean that it is “smarter” than humans. We can’t generalize much about an AI system from performance on any individual benchmark, because the same AI system may perform very poorly when used in other situations where the tasks are even slightly changed.

Why and how was the benchmark made?

Understanding the context surrounding the creation of a benchmark can help you understand intended applications and anticipate conflicts of interest and performance issues. Benchmarks are developed in the AI industry, in academia, and in government labs, each with their own incentives. Because benchmarks have become more influential, they are also increasingly used to bolster marketing for AI systems, which can complicate how people talk about benchmarks and what they mean.

As with the context, it also helps to understand a benchmark’s content. The quality of the data used to construct a benchmark affects the outcomes. Not knowing where data comes from opens you up to risk (e.g., from copyrighted work, explicit material, or incorrect information). Synthetic (or computer-made) data is easier to produce at scale than human-made data, so it is popular to use, but it can also be less representative of the real world.

What are the limitations of the benchmark?

All benchmarks have limitations, by design. They are meant to be standardized, repeatable tests that can be run before an AI system is deployed in the real world. That means that they do not capture how people interact with AI systems once they are deployed or the long-term impacts or risks associated with AI capabilities. (See Benchmarks in the AI Lifecycle diagram above)

Benchmarks are made by people, and people are fallible. The “correct answers” in a benchmark dataset can simply be wrong. The data used to build a benchmark is also limited and may not match or appropriately capture the complexity of real world scenarios. This can show up as bias or “gaps” in what the benchmarks measure, meaning that high-scoring AI systems may not perform well in the real world.

Limitations and failure modes

There are three main ways in which benchmarks can fail, leading to incorrect conclusions about the performance of AI systems:

1

Low quality data

Sometimes benchmarks are built using incorrect data. For example, researchers recently found that in Humanity’s Last Exam, a popular benchmark consisting of graduate-level questions and answers in various fields, about 30% of the biology and chemistry questions had wrong or unsupportable answers. This was due to issues in the question-reviewing process.

2

Flawed measurement or design

Sometimes benchmark targets do not sufficiently capture or measure a target capability, either because the data is not representative of the real world or because the measurement itself is a bad proxy for the capability. (Think about how difficult it is to measure whether a student is a “good student” based on a single score on a single exam.) Benchmark design includes a lot of assumptions about what “correct” behavior is, and different people might disagree on what capabilities constitute a task or what the “correct answers” are.

3

Misinterpreted results

Sometimes doing well on a benchmark is interpreted in a way that exaggerates the capabilities or impact of an AI system. One example of this is in radiology, where early performance on AI benchmarks may have discouraged people from entering the field, when in reality radiologists are still needed, exacerbating a shortage of radiologists.

It is important to be aware of the limitations inherent to benchmarking so that we can use them responsibly. There can be real world harms when people do not properly contextualize benchmark results and what they mean.

Melanomas (skin cancers) present differently on light and dark skin. Many state-of-the-art dermatology AI models are benchmarked using the International Skin Imaging Collaboration dataset, and score highly. However, when one group of researchers assessed popular models against a different benchmark that splits performance metrics by skin tone, they found that performance degraded significantly on darker skin. This difference shows how poorly designed benchmarks or misinterpreted results can misrepresent how AI might perform in the real world and can lead to serious harms.

Looking ahead

Benchmarks are important, but their development and adoption has historically been driven by the goals of AI researchers rather than as targets for AI capability defined by non-AI experts or the general public. The capabilities that benchmarks measure could be improved to better reflect the priorities for what the public wants AI tools to be and do.

Acknowledgements

This work was produced by David Huu Pham, Eleanor Tursman, Heila Precel, B Cavello, Francisco Jure, and Nicholas Vincent, and was made possible thanks to generous support from Siegel Family Endowment.

Share your Thoughts

If this work is helpful to you, please let us know! We actively solicit feedback on our work so that we can make it more useful to people like you.

Contact us with questions or corrections regarding this primer. Please note that Aspen Digital cannot guarantee access to experts or expert contact information, but we are happy to serve as a resource. To find experts, please refer to Finding Experts in AI.

Benchmarks 101 © 2025 by Aspen Digital is licensed under CC BY 4.0.